Introduction: When Christmas Turned Corporate Red

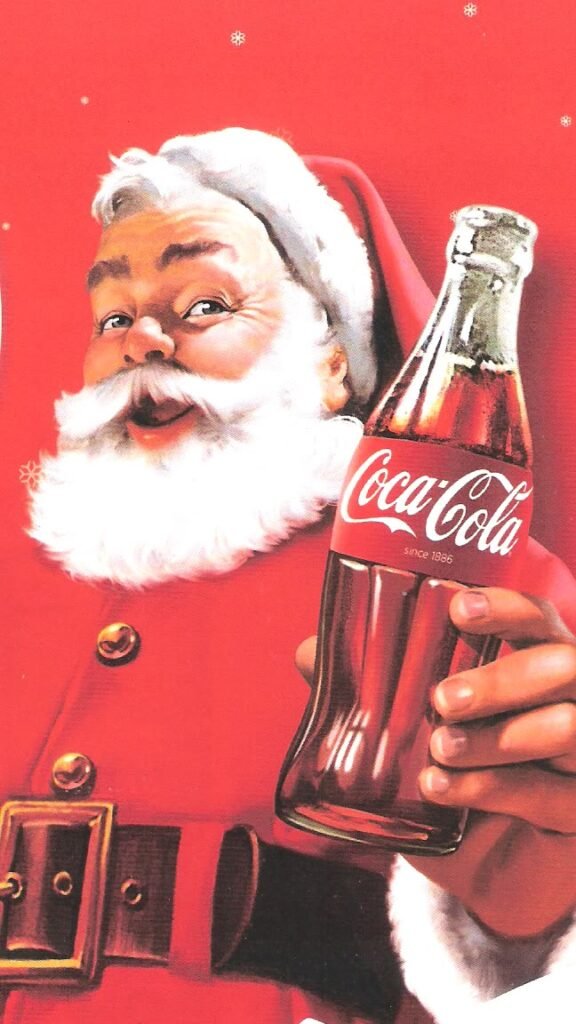

Every December, the world witnesses the same image: Santa Claus in a bright red suit, smiling warmly, spreading joy. For many people, this image feels ancient, almost timeless. Yet behind this familiarity lies a powerful branding story tied closely to Coca-Cola. While the company did not invent Santa Claus or even the colour red in his outfit, it played a decisive role in turning one version of Santa into a global standard. This article explores how Coca-Cola strategically used Santa’s red suit to promote its branding, why this move remains controversial, and how it delivered long-term economic power to the company using real-life historical facts.

Santa Before Branding: A Figure Without a Fixed Identity

A Cultural Character With Many Faces

Before the 20th century, Santa Claus had no single, universal appearance. His roots stretch across European folklore, Christian traditions of St. Nicholas, and regional customs. In different countries, Santa appeared as a bishop, a thin old man, or a mysterious winter spirit.

The Myth of One True Santa

Illustrations from the 1800s show Santa wearing green, brown, blue, and sometimes red coats. Artists like Thomas Nast helped shape early American ideas of Santa, but even then, the imagery varied widely. There was no fixed costume, no global agreement, and no commercial consistency.http://www.stantaclaus.com

The Entry of Coca-Cola: Advertising Meets Folklore

The 1931 Turning Point

In 1931, Coca-Cola commissioned artist Haddon Sundblom to create a Santa Claus for its winter advertising campaign. The goal was simple but powerful: make Coca-Cola feel relevant even in cold months when soft drink sales traditionally dropped

Designing a Friendly, Human Santa

Sundblom’s Santa was different. He was warm, approachable, cheerful, and human-sized—not a mystical or distant figure. Most importantly, he wore a bright red suit with white fur trim, perfectly matching Coca-Cola’s brand colours. This was not accidental; it was strategic visual alignment.

The Power of Repetition: How Advertising Created Reality

From One Image to Global Memory

Coca-Cola repeated this Santa image year after year for decades. Magazine ads, billboards, calendars, store displays, and later television commercials all showed the same red-suited Santa.

Standardization Through Scale

At a time when mass media options were limited, Coca-Cola’s reach was enormous. This repetition slowly erased alternative versions of Santa from popular memory. What began as an advertising choice evolved into cultural “truth.”

Why the Red Colour Mattered Economically

The Psychology of Red

Red is not just a festive colour. Psychologically, red represents excitement, warmth, energy, and appetite. These traits align perfectly with Coca-Cola’s brand identity as a refreshing, joyful drink.

Emotional Branding Over Product Selling

Coca-Cola’s Santa advertisements rarely focused on selling the drink directly. Instead, they sold emotions—family togetherness, happiness, generosity, and celebration. By linking these emotions to the colour red, Coca-Cola turned its brand into a feeling rather than just a product.

The Controversy: Cultural Capture or Smart Marketing

Did Coca-Cola Hijack Santa?

Critics argue that Coca-Cola used its financial and media power to dominate a shared cultural symbol. While Santa belonged to everyone, Coca-Cola’s version became the most visible, effectively overshadowing religious, regional, and historical interpretations.

The Myth That Helped the Brand

Over time, a myth emerged that Coca-Cola invented Santa’s red suit. While factually incorrect, this belief benefited the company by strengthening the association between Santa, Christmas, and Coca-Cola. Even denial of the myth kept the brand at the center of the conversation.

Economic Impact: Branding That Paid for Generations

Building Immortal Brand Equity

Brand equity is the hidden economic value of recognition, trust, and emotional connection. Coca-Cola’s Santa campaigns created brand equity that lasted far beyond the cost of the advertisements themselves.

Seasonal Dominance Without Seasonal Products

Coca-Cola is not a Christmas product, yet it dominates Christmas advertising. This paradox highlights the economic brilliance of the strategy: Coca-Cola became culturally relevant during a season it did not naturally belong to.

Globalization: Exporting an American Santa

Santa as Soft Power

As American films, magazines, and television spread worldwide after World War II, Coca-Cola’s Santa traveled with them. In many countries, local winter traditions were gradually replaced or blended with this Americanized Santa image.

Lower Market Entry Costs

Because people already recognized the Coca-Cola brand through Santa imagery, the company faced less resistance when entering new markets. Familiarity reduced advertising costs and increased consumer trust.

Ethical Questions: Where Culture Meets Capital

The Commercialization of Tradition

The Coca-Cola Santa raises uncomfortable questions. Should corporations be allowed to reshape cultural and religious symbols for profit? When branding becomes stronger than tradition, something intangible may be lost.

Homogenization of Global Culture

Local versions of Santa and winter celebrations have faded in many places. Critics see this as cultural flattening, where diverse traditions are replaced by a single, commercial-friendly narrative.

Defending Coca-Cola: Evolution, Not Theft

Culture Always Changes

Supporters argue that culture evolves naturally and that Coca-Cola simply participated in that evolution. Santa’s image changed many times before Coke, and it will continue to change.

Consumers Still Have Choice

Despite Coca-Cola’s influence, people can still celebrate Christmas in personal and traditional ways. The company did not force acceptance; it offered an image that people embraced.

Reality Check: Separating Facts From Fiction

What Coca-Cola Did Not Do

Coca-Cola did not invent Santa Claus. It did not create the colour red. It did not legally own Santa.

What Coca-Cola Actually Did

Coca-Cola standardized, globalized, and emotionally branded one version of Santa more effectively than anyone else in history. That achievement sits at the intersection of art, advertising, and economics.

Conclusion: A Red Suit With a Heavy Price Tag

Coca-Cola’s use of Santa’s red suit is not just a festive story—it is a lesson in branding power. By aligning a cultural icon with its brand colours and values, Coca-Cola transformed a seasonal figure into a long-term economic asset. The controversy lies not in whether the strategy worked—it clearly did—but in what it reveals about the influence corporations can have over shared cultural symbols. Santa’s red suit today is more than tradition; it is proof that in the modern world, colour, culture, and capitalism are deeply intertwined.